- Home

- Genevieve Hudson

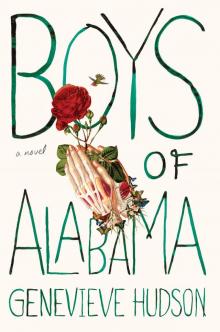

Boys of Alabama Page 3

Boys of Alabama Read online

Page 3

Pan ordered a biscuit with no chicken. It made Max want to eat no chicken, too.

Gracias for the titillating convo, said Pan. Welcome to the U S of A. See you around. I hope.

Pan brushed past him, touching Max’s hip with what seemed like intention.

See you around.

IhopeIhopeIhopeIhope.

Pan in his all-black. Pan with his goth choker and the gel that made his hair go straight up. Pan with the smooth skin he covered in dark brown foundation. Pan with teeth that stayed braceless and crooked as crossed legs. Max stood in line blinking. The cashier had to ask if he wanted butter or bacon with his biscuits twice.

Three times.

Four.

Please yes. Bacon and butter for the biscuit. Please yes.

Max smiled at the cashier.

He arrived late to Physics and found Pan scrawling furiously in an open notebook. The witch had been transferred into his class. Their teacher divined them as lab partners. A miracle, Max thought. No small thing. Pan looked up from the desk, mesmerized as he seemed to be by the grains of wood, and smiled like he expected him. Max shifted under Pan’s gaze, which ran the length of him in one flash. Pan’s cheeks were stamped with freckles. Max never realized chapped lips, held open like that, could look exotic.

One with the biscuits, said Pan. I knew we’d meet again.

Pan kept a collection of comics in his backpack. He pulled one out and placed it in his lap and read it as the teacher lectured. Teacher was orange-skinned with buzzed blond hair and breath of burnt coffee. Pan’s comics were not the adventures of Tintin but comics about monsters and muscled men. The world was always about to end but it never did. Good always stepped in. The day was saved from evil. Heroes existed. Pan fiddled with the choker on his neck, a clipped piece of panty hose. Twirltwirltwirl. Max glanced down at the comic that covered Pan’s crotch but could only make out the word Ka-Pow. Pan giggled as he read the panels. He elbowed Max beside him, as if Max were in on whatever joke he discovered.

Teacher made the class stand up, gather in a ring in front of their desks, grab palms. He showed them how to pass a charge of electricity around the circle by just holding hands. Muscles might spasm when static electricity triggered the nerves. Before class disbanded, an assignment was given. Pan looked at the textbook in front of Max.

Be careful with hot wires.

Pan circled the caution in a paragraph about electricity.

Don’t leave batteries connected for more than several seconds at a time.

AFTER PHYSICS, MAX HEADED to his locker to switch his books. A girl stood by as if expecting him. Her nose turned up like in the movies and her hair framed her face in close-cropped braids.

New boy, she said. Allow me to introduce myself.

A different colored bead sat on the end of each braid. Her name was Glory. When she turned her head, the beads tinked.

How do you know I am new boy? asked Max.

Glory picked at her bitten nails. Hands of someone less confident than she presented.

For real? There’s like fifty kids in each class. Getting a new kid is like getting a celebrity. We get one or two a year. Most of them just sit in the back of the class and look terrified. You get extra points for being an exotic German. But word on the street is your English is dialed in.

Germany is not exotic, said Max. We are not an island. We eat a lot of sandwiches and potatoes. Here is glamorous. The sun is what you have.

Glory was the only girl he’d seen who wore the uniform of a boy. Girls at God’s Way wore skirts or jumpers. Pants were for the boys. Everyone wore a polo with three buttons and the embroidered cross.

Okay, a geography lesson. Word, said Glory. Listen when you need a rundown of shit around here, you come to me. I’ll give you intel on whatever you’re looking to know.

Can you say it again? asked Max.

You got a question, said Glory. I got an answer.

Max stared at Glory.

You play football? asked Glory.

I’m going to be wide receiver.

Cool, said Glory. I don’t know what that means but football is as much religion as religion is around here. Friday nights are all football. You’ll meet Davis. Might have already. Best friend status with Davis is like tying yourself to a social life raft. So, you’re good.

I’m good? Max asked.

It means you did it right. You’re all right. No one is going to mess with you. You decided who you’re going to be.

Football makes me a decision?

Sure does, said Glory.

And do you know also Wes? asked Max.

You can’t say stuff like that here, said Glory. You can’t ask me if I know Wes just because we’re both black.

Is that what Max had done? he wondered. Red crept into his face. He had done a racist thing maybe.

Everyone here knows everyone. Wes’s my brother but that’s beside the point. Just because you don’t know any black people doesn’t mean all black people know one another.

Max opened his mouth to apologize, to find the sorry word. He wasn’t sure if Glory meant Wes was her brother as in biological or brother as in friend. Brother in American could mean both. Glory changed the subject before he could get clarification.

You got a question you want answered. I got an answer. Just remember that. This school is small. I kick it with the public kids mostly. If you ever want to widen your gyre. Let a girl know.

Widen a what?

It’s a Yeats reference. Aren’t you Europeans supposed to be cultured and shit? I’m saying if you want to expand your circle to nonprivate school, I’m your person. Hey—

A girl with a red pigtail on either shoulder and a bright blue monographed backpack walked past them. The air smelled of a boiled meat sandwich. The girl with the pigtails had a cabbage odor, but Glory waved her down excitedly. The girl drove something into Glory and stole her attention. Max was no longer the center of things.

Adios, Germany, she said. Catch you when I catch you.

WHAT CHURCH YOU GO TO ANYWAY? Davis asked, threading his belt through the loops in his jeans.

The locker room steamed around them. Davis looked solid standing as the vapors rose across his chest.

Religion is fine for people who need that kind of thing.

We’re not that sort of family.

Church, said Max. We still look.

Listen, said Davis. If you haven’t been to church before or if your family doesn’t go or something, it’s nothing to be ashamed of. We all start somewhere.

Yes, said Max. Okay.

You don’t have to do what your parents do.

Davis sat down on the bench. The locker room’s steel corridors stood empty, but Max could hear the spray from a running shower and knew they were not alone.

Davis bit into a protein bar and said, Stuff tastes like a cardboard shoe. You want a bite? You’re supposed to eat protein thirty minutes after working out if you want to get swoll.

Max shook his head. He wanted a chocolate bar. The one in his backpack. A dead spider near his shoe. He tried to focus on Davis.

You ever wonder what else there is to all this, Germany? Like you ever wonder what the meaning of it all is?

Yes, Max said. Yes, I wonder.

Davis lifted his face toward Max. Max saw in Davis’s squinting that he’d said the right thing. It was good to wonder. To want more.

There’s church and then there’s God, Davis said. He used a finger, pointed at Max, to hit the end of each word. People get church wrong a lot of the time. But then God comes for you so fast it knocks the wind from you. He sends his spirit to you and you can’t help but go blind.

You go blind? Max was confused. Max had always believed that God, in terms of religious people, helped you see better. God did not obscure your sight.

Yeah, I mean it’s a speech figure, said Davis. It sounds confusing, but you just feel it. Some things are better understood in the body than the mind. Davis placed his hand ove

r his heart when he said body, as if that’s where it lived. Right in the chest. The center of the body breathed. God will send his love to you and you’ll never be alone again. You just make sure you believe—and God, he’ll do the rest.

Max looked down at his hands, which held his chocolate bar, which he hadn’t remembered fishing from his bag. Someone opened the door to the parking lot and a brush of hot air whipped through the room. Max bit into the bar and chewed.

MAX STOOD ON HIS PORCH in his football sweatpants, hair still matted, and sleep crusted in the corners of his eyes. A fresh bruise fattened across his chin. Max pushed the bruise and thought of the boy who gave it to him. He stayed outside for a moment, loving how the rays of morning sun struck him as if to cleanse him. It was a Sunday. Church was where the boys were. He thought of what Davis said about going blind for God. Blindness might steal your literal sight, but Max understood how constriction worked. Other senses would expand to take over the deficiency. Without sight, who knew what you would hear, taste, or smell?

Max touched the ivy that lived on the bricks of his house and considered blindness, a kind of gift. The living green vine curled around a dead yellow sprig. He left the dead parts dead. He would need to run today, he told himself, as he left the browned edges as they were.

Max brought in the paper. By the door, a bouquet of tulips shot their heavy heads out of the end of a vase. He noticed his mother had removed the magnet from the refrigerator—but first, coffee! Max’s mother called church a gateway drug, so he knew better than to bring up his curiosity. He slid the paper from its plastic and spread it across the kitchen table.

Again, the Judge. Front page. The Judge, with his square-shouldered stance, looked nothing like his oafish son Lorne, who played football with Max. He looked like an advertisement for a good father or for testosterone supplements. Max spread his hands over the photograph, over his jaw and the smile lines etched into either side of his mouth. The Judge’s eyes were clear as a stream. They seemed to look up from the rough paper and straight into Max’s soul.

The smell of ground coffee rose through the kitchen. The percolator gurgled and the clink of espresso cups meant breakfast. The table had been set the night before, a routine his mother brought with her to Alabama. Max should have gone to retrieve the yogurt, but the Judge peered up at him. He held eye contact with the Judge as his father filled the table with deli ham, dry sponges of American bread, boiled eggs, and raspberry jam the neighbor had brought to say welcome.

The Judge was running for governor and his campaign announcements were everywhere: taped to restaurant doors, stuffed into mailboxes, pressed into the worn leaves of Bibles that girls clutched to their chests at school. The Judge gazed down over streets from billboards, like he was keeping watch or like he was God or God-sent. Max took a seat and his father picked up the paper to read it.

Look at this, his father said. The man’s campaign slogan is Rise up, Alabama.

Max leaned closer, so he could read the headline. His mother joined them. She had expressed many times how disappointed she was by the tasteless kitchen, the breakable appliances, the tacky stone-look laminate countertops. Her posture conveyed more disappointment. Slouched shoulders, unlike his mother. She peered at the newspaper, too.

A populist thug, his father said. This article says he’s trying to make it mandatory for every resident of Alabama to register with a church or religious organization.

His father whistled as if that was something.

What’s next, a Kristallnacht? said his mother.

Says here he can quote the entire Bible by memory. Entire pages with not a word missing, his father said. Says God places the paragraphs right into his brain.

It’s called a photographic memory, said his mother. And many people have it. It’s not some kind of miracle.

Says here, his father continued, leaning close to the page, he fell from a cliff in his twenties and died. He was left out in the woods wandering around for days as a dead man.

Fell from a cliff? his mother said.

Says he fell the length of seven stories and survived nights out there alone. He ate nothing. On the last day, he drank a can of poison he found in an abandoned shack. After the poison, he saw God and was given new strength and suddenly knew exactly how to leave the woods and find the road to town. God turned the poison into something that healed him.

It’s called a hallucination, said his mother. This man is leading the governor’s race? People believe the story and vote for him?

From his mother’s plate, a piece of unbuttered toast stared at the wooden ceiling. She did not eat it. She looked displaced in the new kitchen and defeated. She had been excited to have more time to paint in Alabama, since she would no longer have her job volunteering at the modern art museum, but Max did not see her easel unpacked or her paintbrushes unrolled on any surface.

Well, it’s an impressive story, his father said. Don’t you think?

His son plays on your football team, am I right? Max’s mother asked, turning to him.

Yes, said Max.

He tried to appear unmoved by the story, but the truth was he found it intriguing. The Judge had cheated death. Death had entered him, and it had not stayed.

I heard him say on the NPR they should teach creationism in schools, said his mother. Creationism. As in God made the world in seven days. Is that what they’re teaching you in science class? Are they teaching you intelligent design or are you learning evolution?

I don’t know, said Max. We haven’t gotten there yet.

You’ll probably never get there, said his mother. That’s how they’ll deal with it. I don’t care what they believe. Honestly, I just don’t want it to affect your education.

What kind of things do these boys talk about on your team? They say anything that sounds off to you? said his father.

No, Max said. They just talk normal stuff. Boy stuff.

Boy stuff? said his mother.

His mother snorted and whacked the top off her boiled egg with the back of her spoon, splitting the shell. His father took a sip of orange juice and stood up, groped his pockets for something.

Okay, he said. Well. I mean, I’ve never met the man. But his story is a tall tale if I’ve ever heard one.

People love a story, said his mother.

His dad shrugged as if he wasn’t sure and didn’t care.

Max regarded the Rorschach blob of jam smeared across his yogurt. On the face of his breakfast, Max saw a raspberry boy sprinting across an organic, whole-milk field. He saw a seedless red cross rising up behind him as he ran. He saw a risen Judge bleeding life into a white sky.

AT WALMART, MAX FELT SMALL in the huge expanse of space. The shelves were filled with American treats like peanut butter cups, candy corn, and marshmallow squares his mother would never let him eat in Germany. He walked past pyramids of Kit Kat bars and displays of vacuum cleaners and shelves filled with condoms and strawberry-flavored lubricant. He walked past a wall of television sets playing three different football games. The television faces spoke in silent sentences to no one in particular. He stood in the middle of an entire aisle of Bibles. He’d never known there could be so many different kinds of Bibles. Max could have bought guns and two-liter bottles of Coke and lawn chairs in one trip. He could have bought anything at any time, because Walmart only ever closed one day out of the entire year, Christmas, Jesus’s birthday. He wasn’t in Germany anymore. He knew it for sure as he stood in aisle 7 under the hiss of the bright white lights. He wanted to fit in, Max realized, as he touched a bag of Cheetos.

You fast as a Cheeto, Knox had said. The memory made him smile. A cartoon cheetah with sunglasses stared at Max from the front of an orange foil bag. Dangerously Cheesy, promised the cartoon cheetah.

Max used to love going with this mother to the market in town for dark bread. It would still be warm from the oven as they carried it home. He could feel the weight of it in his hand now, heavy as a potted plant. He stood in the Wal

mart bread aisle, which smelled of nothing, especially not bread. The sterile, plastic-wrapped loaves sat slack on the shelf. There seemed to be more things to buy in Walmart than people in town to buy them. Who, he wondered, would purchase all this bread? All these TVs? All these guns?

Max asked a Walmart employee where he could find the fried chicken. The salesperson wore a scoutlike vest with many patches of smiling yellow faces pinned all over it. how may i help you? was written in bubbly font on his back. He looked too old to be working a service job. To be working at all. He walked with a plastic cane. He kept calling Max sir. Like—Yes, sir. I can show you where the chicken is, sir. Max felt he should be the one calling him sir, since he was younger, but he went along with it. Before he walked away, the man raised a speckled hand and said something that sounded like Haffagoodunnowyahhere. Max nodded and that seemed to be enough. The chicken sizzled and steamed in a paper bag below a row of blistering lights. The bag fumed as he carried it to the checkout line.

His mother drove him to Davis’s house. Max could not drive in Alabama. He did not have a license and his parents weren’t keen on him getting one anytime soon. The other boys could drive and owned their own vehicles, which they drove to school themselves and let bake on the black asphalt lot. They waited like treaded chariots. That’s freedom, thought Max. To be sixteen and own a car.

Davis’s house loomed at the end of a cul-de-sac, surrounded by smaller, lesser houses with fewer levels and puny yards. Max counted three stories out loud with his mother in the car. Sunlight hit the clean, white paint and glinted against a wide, screened-in porch where potted ferns and sculptures of rattan elephants guarded a rocking chair. Max readied to knock on the front door but voices beckoned from the backyard.

There he is, said Davis, when Max walked into the barbecue with the exact right thing. Coach surrounded Max in a hug that contained much slapping. His back stung from the flat hand hitting him.

Boys of Alabama

Boys of Alabama