- Home

- Genevieve Hudson

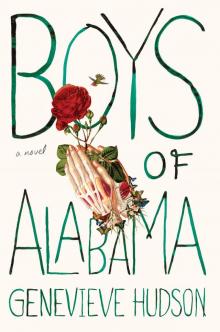

Boys of Alabama

Boys of Alabama Read online

ALSO BY GENEVIEVE HUDSON

Pretend We Live Here

A Little in Love with Everyone

CONTENTS

Parte 1

Parte 2

Parte 3

Acknowledgments

For my parents

She believed in angels, and, because she believed, they existed.

—Clarice Lispector, Hour of the Star

THE BOYS ARE ALABAMA. They are red dirt and caked mud. They are grass stains on knee pads, names on the backs of jerseys, field goals and fullbacks, Heisman trophies and touchdowns, a fat lip and a happy concussion. They are pine trees ripped up to make room for gas stations, stadium lights, drive-thrus, gridirons, and steel mills. Alabama wasn’t built by them, but the boys swell with pride, a rabid and real thing like peanuts planted in the fields that they can harvest. Their trucks roll over roots and through dry creek beds and their bellies bulge with the surplus of it: the grain and corn culled from the ground that God watered for them. Their muscles remember the past. They know how to gut a deer, how to slice a fish, how to tear cotton from the stem, how to tighten a fist in the middle of a hot house and lie.

Rivers run fast in Alabama and sometimes as slow and sleepy as one of those rocking chairs abandoned on a porch where women used to sip sweet tea and wait. Wait for something that isn’t coming, because nothing comes to Alabama anymore except for you.

PART 1

FROM THE PLANE, ALABAMA UNFURLED in green fields and thick forests. Wilder than Max had pictured. Trees went in all directions and houses were hidden among them. He touched his nose to the glass window. The aerial engines whirred. The plane banked against a shelf of sky. The landing gear slammed into place, and his mother, the fearful flier, gripped the hand rest between them. She slid her fingers over the back of Max’s wrist. They descended over a neighborhood of slanted clapboard shacks that leaned toward one another, strewn junk going rotten in the yards.

You’ve got the good seat, said his father. The plane lowered and lowered. Front row to the action.

In the airport, Max’s family bought sweet teas served in Styrofoam cups so big he had to hold his with both hands. He drank half of it and felt high. Sugar soared through him. He bought a disposable camera in the terminal kiosk from a man with marble eyes and a baseball cap with an Alabama A. Max had attended an exhibition in Berlin the previous month where an artist made collages out of pictures developed from a disposable camera and construction paper. The fuzzy, low-res images had created a nostalgic quality out of dried toast and lonely mandarins. Max held the green plastic camera in his hand. Its picture quality would pale in comparison to the power of his phone, and that was the point. Max wanted to document the drive to his new home. He wanted the pictures he took to look sentimental and unsettled.

Outside the air hung in sheets. It was heavy when he swallowed it and left a taste in his mouth he didn’t know how to identify yet. His nose started to run, his legs to sweat, and his breathing moved up into his throat. As they waited for their rental car, his family stood beside a group of men whose skin shone a porkish pink.

On the drive to their new town, Max’s mother mumbled, Oh, it’s actually quite beautiful, and Max agreed.

He thought the landscape was exotic, all those red rivers they drove past, rushing like arteries cut open across the earth. The sky was burnt blue and the trees were jagged things that huddled together. Forests fattened along the sleepy highway. Max tried to look through the trees to see what was back there, but he only saw rows of more pines pointing upward, reaching. Some had signs stapled to their trunks that warned KEEP OUT and NO TRESPASSING and SMILE YOU ON CAMERA. Others had fallen horizontal, their roots severed like veins, as if a storm or some terrible force of nature tore them from the soil, and no one had cared enough to clear them away.

They passed a billboard advertising BBQ ribs. Then a billboard advertising the Bible. A truck with monster wheels boomed past. It flew a Confederate flag from its bed. Max knew the flag from the movies, but here it was in real life. The line on a bumper sticker: GOD BLESS OUR MILITARY, BUT ESPECIALLY OUR SNIPERS. The family drove for almost an hour with their chests tipped forward. The rental car smelled like Hawaiian Aloha, a scent his father had chosen. A football-shaped air freshener swung from the rearview mirror. This is where the Hawaiian Aloha smell originated.

His mother flicked it and said, Aloha headache.

His mother lit a cigarette and blew a line of smoke at it.

The sunset was enough to make them pull over and step onto the shoulder of the road. Max brought out his camera and his father snapped a picture of him flexing his muscles in front of I-20. A glow stretched across the horizon and electric purple clouds pulled apart like sweet taffy. In Alabama, the sunset held an extra charge, everything did, because everything was new. The pink particles of light wielded their strange power. The sky appeared bigger. Maybe it was.

When the car plant came into view on the left, Max’s father jabbed a thumb at it. That’s where he would be stationed. The main building was German-looking, white, and clean, with a sleek roof made to mimic a series of coastal hills. The sterile campus and its familiar design relieved Max. He turned his head and stared as the buildings shrunk into the distance.

His father took the exit into town—WELCOME TO DELILAH—and began to laugh. Max wondered if he should laugh, too. Something about the scene did seem funny. It was funny that they had arrived. This was it. The car slowed to an inch in front of a series of traffic lights. In the truck next to them, a hard-jawed man in a cowboy hat hung an arm out the window and ashed a cigarette. They were home, if you could call it that yet. On both sides of the street, neon signs pulsed with life. They beckoned with taco burgers, catfish platters, frozen yogurt parfaits, and paper cones of popcorn chicken. There was so much brightness, Max could have forgotten it was night.

They drove down a road named after a legendary college football coach who’d led the team to many national championships decades ago. His father had heard of him. All the way in Germany he knew of the man whose street they drove down. His father seemed impressed by his proximity to the dead man’s legacy, pleased with himself for knowing.

If you want to understand this place, you need to understand the pride they have for this man, his father said. He gave them hope. And hope is a remarkable thing to give.

They passed the high school Max would attend, a prisonlike sprawl of low buildings flanked by green fields, named God’s Way. The school was a private evangelical school, and although Max’s family was not religious, the school had been recommended to them by his father’s new colleagues.

The public schools here are full of violent kids.

There’s at least one stabbing in the cafeteria each year.

Everyone’s daddy’s got a gun.

All the boys know where to find the gun.

He’ll get a better education in private.

The teachers are more invested.

We aren’t going to be able to provide housing in a good school district.

Whether it was true that the schools were as violent as they’d been told, the word gun scared Max’s parents into obedience.

The houses in the neighborhood frowned at Max from their perches. The space between the yards excited him. The suburbs. American largeness. The homes looked like they had fallen asleep, their curtains drawn, their interior lights a drowsy blue. Inside the rooms of the houses they passed, Americans did American things.

Max felt television-famous when his father pulled their rental car into the circular driveway of their new house. Houses like this existed only in the sitcoms that came careening into his TV. Ivy climbed and curled up the redbrick face, past two stories of shuttered windows. In Germany, houses

this big were reserved for the rich. A stone settled in his stomach when he thought of Germany, all those hours behind him now. He remembered the two Americans he had seen on a bus in Hamburg just days before and how he hadn’t been able to stop watching them: their too big pants and the confident grins affixed to their boyish faces. They had seemed assured there in a foreign city, as if it, too, were theirs. Now Max was in America, but he did not feel that it was his.

In his new backyard, blond slates of wood formed a perfect square fence. It reminded Max of a story he had read about an American boy called Tom Sawyer and how Tom’s evil aunt forced him to whitewash a fence as punishment for skipping school. But Tom made the work seem like an honor and fooled boys into painting the fence for him. American boys are clever, thought Max. And they want to trick you. Max visualized himself washing this fence white, making friends from it. Friends. He could not imagine. His parents reeled through the rooms inside. They called out for him, but Max stayed in the backyard, taking in the purple night that seemed to glitter with kicked-up dust. He bent down and stared at a blade of rotten grass.

He still spotted dead things right away. Dead grass looked the same here. He plucked the blade. In his fingers, the brown grass turned green. The taste of peppermint filled his mouth. He swallowed the sweetness down, pinched the blade of grass to the wind, and let it go. He almost expected the chlorophyll to stain his hand green as punishment. Shame washed through him. He thought of Nils in his coffin. Cold dead body, cold stretched skin. No, he told himself, smoothing the front of his khakis with his palms. He formed a fist with his entire body and clenched it tight. He wouldn’t do that here.

MAX’S HOUSE STOOD AGAINST THE back edge of the neighborhood. A highway bent close to it, hidden by sight, but not sound. Max couldn’t picture where the cars went, but he wanted to know. They might lead to parties with American boys. To 24-hour diners. To anywhere he didn’t know yet. All night Max turned and twisted to the sounds of engines, the occasional hot shriek of a horn, the skid of tires over black pavement. He stared at the plaster ceiling. In Germany, their street had been quiet. He had heard his father cough down the hall, the squeak of his mother’s feet on the stairs, nothing more. He had heard neighbor voices, Nils’s mother, moving through their open windows into his.

On his first morning in Alabama, birds cried in the trees outside Max’s window. Their song was neither happy nor sad. He ran his hand along the sheets. They smelled like eucalyptus, like a detergent called Sunshine. He tried to miss something about Germany.

He walked downstairs, through the cool, open living room. The house seemed breakable, almost flimsy in its construction. Nothing like the solid brick home his family had in Hamburg. Their new rental had come furnished, but the house looked somehow familiar to him in the daylight. It was every house he’d ever seen in an American movie. The words Sweet Home Alabama had been cross-stitched in crimson and hung above a fireplace made from river rock tiles. He touched the birch of the frame and thought home. But it sounded more like home? in his head. The couch held large pillows upholstered in blue stripes. He imagined the nap he would take on it later. He rubbed his temples. The ache was back. Claws gripped the corners of his eyes. He held up his hand to study its subtle tremor. Still there.

The couch faced a flat-screen television. The walls around him had been painted daffodil. Cheery like outside. An antique bowl sat on the coffee table. Grapes spilled over its sides. Max pinched one grape and watched it ooze. He thought of an eyeball plucked from a face. He picked another grape and placed it inside his mouth. Sweet burst of green on the tongue. A distraction in the body. He craved sugar again. All it took was one blade of grass and the symptoms rose up in him. He almost missed the comedowns, the hollow of exhaustion that overtook him, the headaches that sent him to sleep. No amount of sugar or exercise or afternoons spent in dreams could serve as enough balm to distract him from his most base desire. Max sunk his bare toes into the thick carpet. Carpet. The tacky, bandage-colored material covered all the floors.

Max walked out of the front door, which was two doors and not one. A wooden door then a screen one. He squinted into the brightness and inhaled the smell of dug soil. He felt eyes press into his back. Someone was watching him. He turned to see a neighbor woman in her garden.

Y’all must be the new Germans, the neighbor woman said.

She stood with her hip cocked to the side, grinning temple to temple. Her voice had a drowsy quality that Max wanted to curl up against.

We wondered when y’all would show up. The old Germans said new Germans would be coming soon. Never could say their names right so I just called them the Germans. Hope you don’t take offense to that.

Nine a.m. and the neighbor woman held a diet cola. She walked over to Max and extended five fingers tipped in red talons. Max shook her leathered hand, which went limp at his touch.

Honey, look at you already sweating.

She laughed but not at him.

How to say it, he said. It’s very, what is the word, wet.

Humid! she said. Honey, don’t I know that.

She had slathered her face in makeup and wore flip-flops bejeweled with rhinestones. Her hair hung in loose, self-imposed curls. Most bizarre to Max was that she wore an oversized red football jersey. The rest of her outfit seemed to call for another kind of shirt, a blouse of some sort, anything besides a sports uniform. Max liked her right away. He hardly understood a thing she said but her eyes sizzled and cracked with life. They seemed to say FUN. Max’s mouth twitched, as if he had no choice but to smile, too. Her name, she said, was Miss Jean.

Y’all better come over one Saturday to watch a game. Too much excitement to miss. The season’s not too far off now. So y’all mark it on your calendars, you hear?

Please? Max said. Can you say it one more time?

The word y’all confused him. The phrase you hear.

Miss Jean didn’t answer. Something else sat in her mind.

Saddest thing. That’s Tammy’s house. Was Tammy’s house. See it?

She pointed toward the cul-de-sac where a police car nested in front of another brick house. Max squinted.

I don’t mean to gossip with you, she said. Her voice dipped into conspiratorial tones. But what kind of neighbor would I be if I didn’t say something? Aneurysm killed her in the middle of the night.

What? Max said.

Killed?

Now tell me how in the Sam Hill does someone as healthy as Tammy fall down dead out of nowhere? I can’t pretend to understand it.

It sounded sad but Miss Jean recounted it in a singsong voice.

Someone died? asked Max. On Sam’s Hill?

I wouldn’t worry about it, hon, I’m just telling you to keep saying your prayers each night. Keep on praying. We never know what God has in store, now do we?

Max did not mention that he didn’t pray, had never once in his life thought to pray.

The screen door hit its hinges.

Max’s mother called to him from the porch.

Max, will you to introduce me to your new friend?

It was strange to hear his mother’s English, but he guessed he’d get used to it here. She walked up to their neighbor to say hello, and Max marveled again at her command of the language. Her confidence with the American words in her mouth. His mother looked odd beside Miss Jean. Her cropped black hair and swooping bangs did not flatter her in the morning light. Next to Miss Jean’s coin-colored face, smeared in bronze blush and golden eyeshadow, his mother was plain and underdone. Her lips looked sucked of color.

You speak such good English! You sound like you’re from Australia. Not Germany!

His mother had studied painting in London for graduate school, and her English arrived in a British accent. His parents had met in an expat bar in North London and lived there for many years before moving to a small studio in Paris’s Twelfth Arrondissement, where they would have continued their international life with their international friends if his mother had not

gotten pregnant and his father had not taken a practical job offer in his hometown in Germany to support a new family.

I don’t know about Australia, his mother said. But thank you.

The old Germans did not speak English this good is all I’m saying.

Miss Jean recommended breakfast at the Touchdown, and that’s where they went. Eating out for breakfast! A rare occasion to mark a rare day.

A WAITRESS with a meringue of yellow hair wearing what appeared to be a cheerleading uniform led Max and his family to a table set with jars of sugar and hot sauce. Photographs of the college football team were tacked from ceiling to floor. Grainy images from the early 1920s showed players in leather helmets and wool sweaters. In more recent pictures, sleek uniforms stuck in sweaty patches to the curves and divots of the players’ shoulders and stomachs. Their arms were raised in V’s for victory. They had won, won, won. It appeared that they were always winning. Even their grins were winning.

A dozen national championship flags hung from a beam by the kitchen. Max let his eyes linger on the lore affixed to the walls: the stuffed elephant mascots, the old-time ribbons decrying greatness, the lyrics from a fight song scrawled on the back of a famous quarterback’s shirt. Portraits of coaches shouting, discourteous, praying beneath a flag. WHO BELIEVE IN 2009???? was scribbled across a large poster board. Under it lived the names of every fan who knew their team would take the championship that year.

The photograph above Max’s table showed a bird’s-eye view of the college campus. The football stadium reached over the top of even the highest building, like the university’s castle. Lights pointed their golden faces toward it, as if to italicize its significance. The campus was in another town about an hour away. But its lore, the storied football team, reached all the way to Delilah and beyond. Pride raced down every red dirt road in Alabama.

Max’s father whistled and flicked his fork toward the frame.

Boys of Alabama

Boys of Alabama